Albert Hofmann and the psychedelic bicycle

It was on this day back in 1938 that Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann first synthesized the psychedelic drug LSD, or lysergic acid diethylamide.

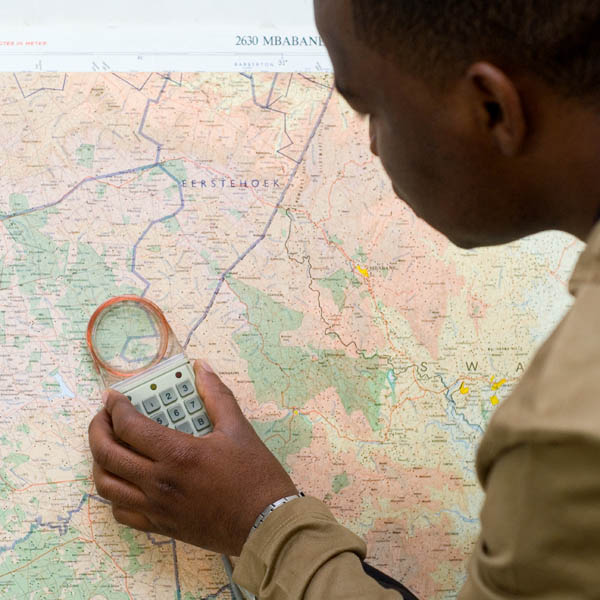

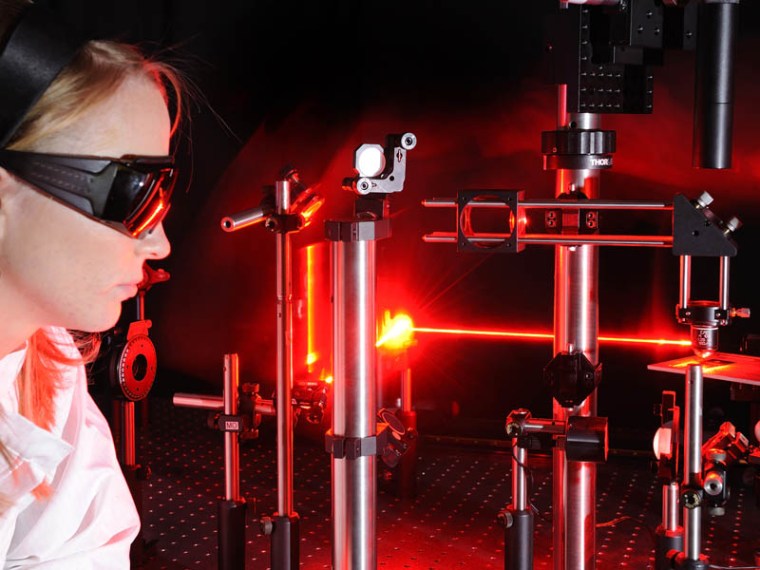

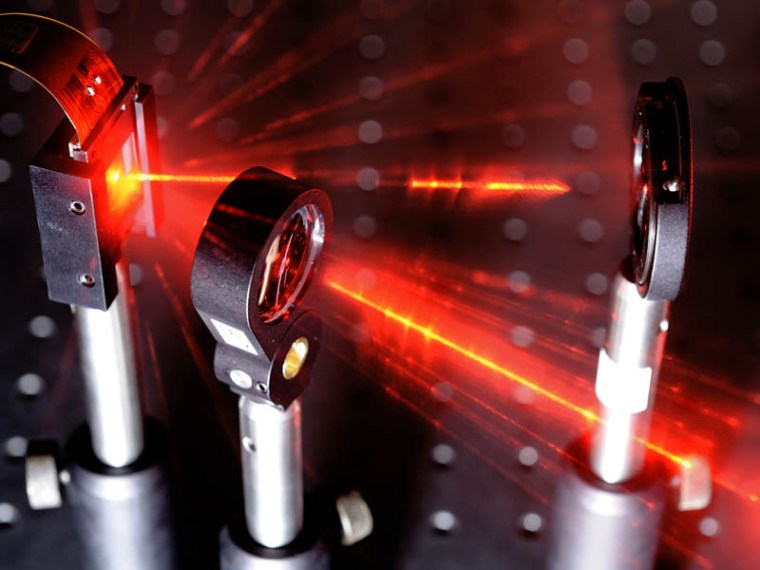

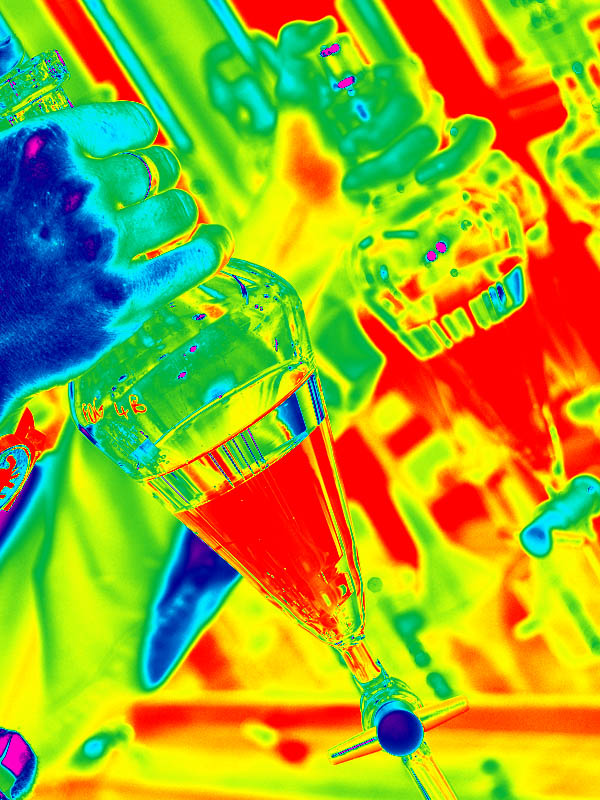

The story goes that Hofmann, working in the pharmaceutical-chemical department of Sandoz laboratories in Basel, was investigating the purification and synthesis of active constituents from the squill plant and ergot fungus, for use in new pharmaceuticals. While studying derivatives of lysergic acid for use in a respiratory and circulatory stimulant, he synthesized LSD, a semi-synthetic derivative of ergot alkaloids. The newly discovered drug apparently didn’t show much promise, as the project was set aside for 5 years until 1943, when Hofmann decided to return to it for some further investigations. After re-synthesizing LSD, a small amount of the drug was absorbed in his body when it accidentally came in contact with his fingertips.

It was this accidental contact that illustrated the potency of his discovery in a most vivid way. His notes on the experience included the following description:

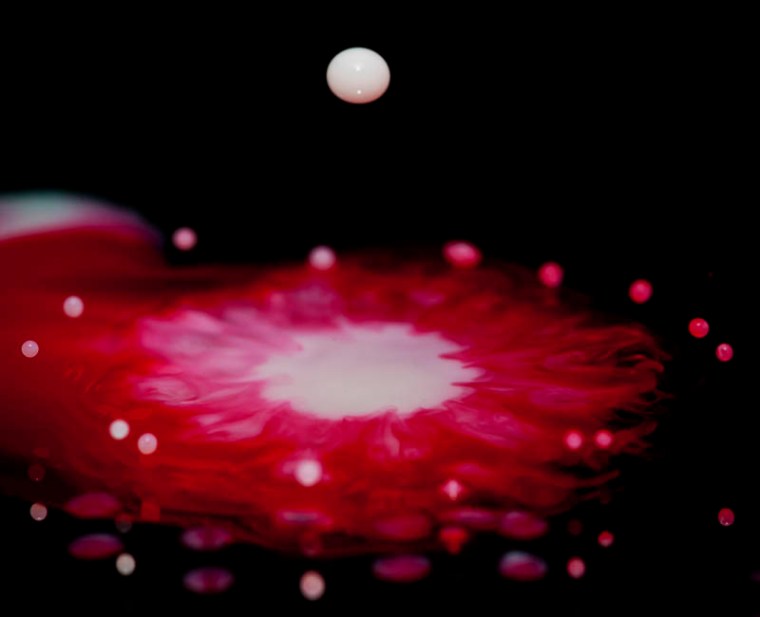

“At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterized by an extremely stimulated imagination. In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors. After some two hours this condition faded away.”

(© All Rights Reserved)

Impressed by its power, he decided to study it in more detail, and on 19 April 1943 he performed a self-experiment, ingesting 0.25mg of LSD. Within an hour he started experiencing an extreme reaction and requested his lab assistant to escort him home. As wartime restrictions prohibited the use of motor vehicles, they had to make the journey by bicycle. During the journey home Hofmann experienced severe hallucinations and heightened anxiety, fearing that he poisoned himself. His house doctor was called in, but he could find no physical abnormalities, except for very dilated pupils. This gave Hofmann some reassurance, and after a while his anxious state subsided, giving way to a state of hallucinatory euphoria where he again experienced vividly coloured and constantly changing dream-images.

Hofmann, realising the potency of the drug, felt it had huge potential as a psychiatric tool. Given the intensity of his experience, he had no inkling that anyone would consider using it recreationally.

(He was clearly wrong on this point – his experience, dubbed ‘Bicycle Day’, became famous in drug history, and continued to be celebrated enthusiastically in psychedelic communities many years later.)

After Hofmann’s initial experience, interest in LSD soared, and over the next 15 years it was the subject of extensive studies, becoming the topic of hundreds of academic papers and even entire scientific conferences. It became used in psychotherapy, treatment of depression, and as a supposed cure for alcoholism. At the same time, the CIA also became interested in the potential of the drug for their applications, funding a project known as MK-ULTRA where subjects (many unwittingly) were exposed to the drug to test its effects. This highly controversial project, that continued for almost two decades, included investigations on the potential for various drugs in combination with stress or specific environmental conditions, to break down prisoners or induce confessions, and had a lasting psychological impact on many of its subjects.

It wasn’t long before the popularity of the drug went beyond its medicinal application. Initially psychiatrists started using it recreationally and sharing it with their friends., and by the early 60s its recreational use had gained much wider popularity. It has had a huge influence on music and art, particularly the psychedelic movement of the 60s. LSD had a number of highly visible and vocal supporters, including one-time academic turned LSD guru Dr Timothy Leary, and author Ken Kesey (whose experiences as part of the CIA’s MK-ULTRA programme became the inspiration for his “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest”)

By April 1966 LSD had become so popular that Time magazine, who had published a number of positive reports on the drug in the 1950s, published a warning about its dangers. At the same time, the US government stepped in and declared the drug illegal, giving it a Schedule 1 (“high potential for abuse”) status. California banned the drug in October 1966, with other states, and the rest of the world, following soon after.

(© All Rights Reserved)

I can only wonder what Albert Hofmann, working in his lab in the late 1930s, would have thought if he could have had a glimpse into the future to see the range of effects and applications of the drug he was working on. In chaos theory, the example is often given of a butterfly flapping its wings in one part of the world potentially being the impetus for a massive storm thousands of miles away, but I think the image of Albert Hofmann’s laboratory research in the 1930s resulting in a psychedelic festival of music and culture in the 1960s, would be an equally vivid illustration!